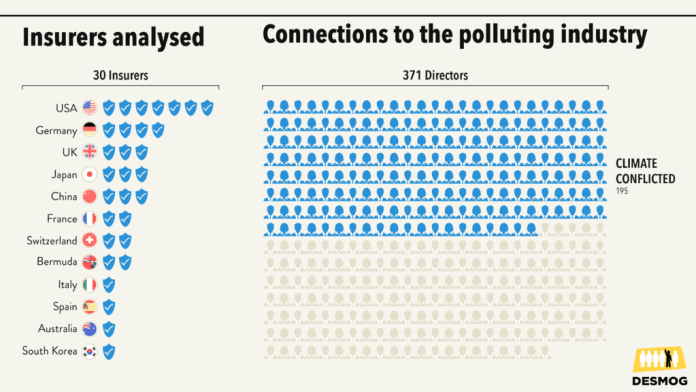

Just over half of all directors at 30 of the world’s largest insurance companies have affiliations to polluting companies and organizations, reveals an investigation by DeSmog, including several individuals holding senior roles at some of the world’s largest energy companies.

The findings raise concerns over a potential pervasive conflict of interest on the boards at a time when the international insurance sector is under pressure to halt its support for the fossil fuel industry.

Positions held by the insurance directors analyzed ranged from director and advisory roles, including current roles at ExxonMobil, Total, and RWE, along with current and former memberships to industry trade association and think tanks, such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

DeSmog analyzed director CVs on company profiles, LinkedIn pages, official filings, and news clippings from July 2021, logging the past and present work experience of 371 insurance directors who currently sit on the boards of 30 of the world’s largest property and casualty insurers.

The research reveals that 53 percent of these directors have a combined 499 past or current connections to industries that could be considered potentially climate-conflicted including polluting energy, mining, manufacturing, along with banks and investment vehicles known to support the fossil fuel industry.

Just over one in ten directors across the insurers analyzed worldwide had experience at companies operating in fossil fuels, including oil and gas companies, a major coal developer, and utility companies relying on fossil fuels for the power they produce. In the U.S. this number jumped to one in five board members across the insurers analyzed.

The links revealed by DeSmog’s analysis may show a “revolving door” between insurers and high-polluting industries that may explain why, despite the risks, the sector has been slow to act on climate change, said Lucie Pinson, executive director at the environmental campaign group Reclaim Finance, reacting to the findings.

“When insurers underwrite fossil fuels, they actually are underwriting climate change.”

Yevgeny Shrago, a policy counsel in climate change for advocacy group Public Citizen

The investigation focussed on directors as they are the ones with ultimate oversight over strategic and regulatory decisions for the insurance companies. Among their powers, directors have the ability to vote on resolutions which dictate key decisions made by the company at annual general meetings. In recent years these meetings have been targeted by activists and investors calling for insurers to stop supporting the fossil fuel industry.

The revelations come as a growing number of insurance companies have announced they will limit the services they provide to the most polluting fossil fuel projects, such as by limiting or ending the insurance they provide for coal and tar sands projects.

Despite a growing trend away from the most-emitting developments, however, nearly all leading insurers, including those analyzed, continue to provide insurance coverage for oil and gas projects and many still provide at least limited support for coal developments, including through what campaigners have said are “loopholes” in their coal exclusion policies.

Only one insurer in the world, Australia’s Suncorp, has announced it will restrict its support for oil and gas projects worldwide, according to a report from campaigners at Insure Our Future ranking the climate policies of major property and casualty insurers last year. While Suncorp was not included in this analysis, many of the same companies in DeSmog’s analysis feature on the ranking.

For years, experts have warned that under strong climate action to limit temperature increase below 2 degrees Celsius, the world must dramatically limit the extraction and use of fossil fuels. This means fossil fuel projects could become financially risky “stranded assets,” according to analysts.

“There are two major sets of risks for insurers being involved in fossil fuels,” explained Yevgeny Shrago, a policy counsel in climate change for advocacy group Public Citizen.

“The first risk is what we call transition risk,” Shrago said. “These are assets that are going to lose their value very quickly” and unpredictably. While an insurer invested in fossil fuels currently may be getting a large return on them now, Shrago said, this could change at any moment.

“The longer term risk we see,” Shrago continued, “is that when insurers underwrite fossil fuels, they actually are underwriting climate change. The IPCC is very clear that every fraction of a degree matters when it comes to averting physical risk.”

“What that means is that if an insurer enables a new fossil fuel project to go forward, it’s actually then contributing to increased climate harm. Increased climate harm means higher insured losses and greater pressure on solvency in the future.”

DeSmog’s findings on the experience of directors’ on insurance boards may help illuminate why, despite the risks, the sector had been slow to act, added Shrago.

“There’s actually a premium for insurance companies to stop insuring coal, stop insuring oil and gas, exit those industries, and yet they continue to do so. Which raises the obvious question, why? Why are they still doing that?” Shrago said.

Ties to Big Oil

A deeper look into the data shows that roughly one in ten directors had past or current ties to the polluting energy sector. And 6 percent of board members overall were found to hold current roles in the fossil fuel industry, including through board memberships at major oil companies such as ExxonMobil, Total, and RWE. Among those with current ties are also individuals with roles at utility companies, such as Italy’s Enel or Eversource in the U.S., which generate their energy from fossil fuels including controversial and heavily emitting sources such as coal and fracked gas.

Responding to the findings, Elana Sulakshana, senior energy finance campaigner at the climate advocacy group Rainforest Action Network, said: “Insurance companies can play a crucial role in accelerating a transition to a clean energy economy, but it’s highly concerning that their boards are so entangled with fossil fuel interests.”

“Insurers cannot credibly claim to be climate leaders, while being governed by executives who have a personal stake in the continued expansion of coal, oil, and gas infrastructure,” said Sulakshana.

US insurance giant Liberty Mutual had the board with the most ties to the fossil fuel sector, with eight out of its 14 directors linked to major polluting energy companies. The insurer’s directors hold current board memberships at Koch Industries, Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL), ExxonMobil, and utility company Eversource Energy which services Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, and has been targeted by campaigners for its support for the natural gas industry.

Liberty Mutual board member Annette Verschuren, for example, began her career in the Canadian coal industry and is now a director of the Canadian oil and gas company, Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL), which extracts fuel from Canada’s highly polluting tar sands. Verschuren’s fellow director at Liberty Mutual, Joseph Hooley, has been director of the United States’ second largest oil company, ExxonMobil, since 2019. And three further members of the Liberty Mutual board are current trustees of Eversource Energy, while a fourth is the utility’s former CEO.

At the end of 2019, Liberty Mutual announced restrictions on the type of support it provides to the coal industry. Currently, however, it has no restrictions on its support for the oil and gas industry. The insurer is under pressure from campaigners to end its support for the tar sands industry, including the TransMountain pipeline extension, which will be used by CNRL.

“Liberty Mutual is one of the biggest fossil fuel insurers in the world, and the fact that over 40 percent of their board members are also on the boards of fossil fuel companies helps explain why the Boston-based insurance giant has been so resistant to changing that,” argues Sulakshana.

Liberty Mutual did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

The other boards with the highest number of ties to polluting energy companies were Italian insurer Generali, where four out of 13 directors had experience in the energy industry and Swiss insurer Zurich where three out of 11 directors previously held roles at oil and gas and utility companies.

Generali director, Diva Moriani, was a director of Italian multinational oil and gas company, Eni, from 2014 to 2020.

A Generali spokesperson said coal, oil, and gas production “stood at less than 0.1% of its P&C premiums.” The company, they said, aims to gradually decarbonize its investment portfolio to reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

Zurich director, Dame Alison Carnwath, meanwhile, was a director of British oil giant BP until January 2021 when she resigned for unspecified “personal and professional reasons”.

A Zurich spokesperson said the company sees the “diversity of expertise” on its board “as a critical success factor for the performance of the board, as different views and ways of thinking lead to better informed decision making.”

They added: “We strongly believe that we can have the biggest impact by using our influence as an insurer and investor through engagement with our customers and the companies we invest in to promote a rethinking and the adoption of business models aligned with a 1.5C future.”

Elsewhere in Europe, AXA-director, Patrizia Barbizet, has been director of the European oil giant TotalEnergies since 2008.

AXA did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

Coal Connections

Meanwhile, eight insurers had board members with past or current experience in companies involved in extracting coal as featured on the Global Coal Exit List produced by Urgewald, a German environment and human rights NGO, to track companies’ involvement in the global coal supply chain.

This includes Swiss Re director, Raymond K. F. Ch’ien, who is a current director of China Resources Power Holdings Co, a Chinese company that develops and operates coal plants across several Chinese provinces.

A spokesperson from Swiss Re said “Swiss Re’s board members have been selected against comprehensive criteria in various areas. They are fulfilling their mandate at any time in the best interest of Swiss Re.” Among the board’s responsibilities is overseeing the company’s sustainability strategy.

The Swiss RE spokesperson added that starting in 2023 the company will introduce insurance policies to restrict its exposure to coal. The aim is to eventually reach “a complete phase out of thermal coal exposure in OECD countries by 2030 and in the rest of the world by 2040.” And starting this year the company says it has also “gradually started withdrawing insurance support from the world’s 10% most carbon-intensive oil and gas production” to be completed by 2023.

Tokio Marine Holdings director Masako Egawa, meanwhile, is a current director of Mitsui & CO, a Japanese General Trading company featured on the Global Coal Exit List for its holdings in Australian coal developments.

Tokio Marine Holdings did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

“Insurance companies must ensure that their boards are equipped to address the escalating climate crisis.”

Elana Sulakshana, senior energy finance campaigner at Rainforest Action Network

And The Hartford director Michael G. Morris was president, chief executive officer, and chairman of American Electric Power (AEP) from 2004 to November 2011 and continued as AEP’s chairman until 2013. American Electric Power is one of the United States’ largest generators of electricity, and generates nearly half of its electricity from coal.

A spokesperson from The Hartford pointed DeSmog to the company’s 2019 announcement that it would no longer support companies which generate more than 25 percent of their revenues or energy production from coal or more than 25 percent of revenues directly from the extraction of tar sands oil.

Speaking generally about the insurance The Hartford provides, they said: “We have long understood we have a special role to play in response to the climate emergency. Extreme weather affects people’s lives and businesses – and the risks are getting worse. Helping people prepare and adapt to climate change is essential to The Hartford, and our customers.”

Another example is Hannover Re supervisory board member, Erhard Schipporeit, who has been a supervisory board member of Europe’s largest polluter, RWE since 2016; RWE generates nearly a third of its energy from coal, including brown coal (also known as lignite). Coal is the world’s most polluting fossil fuel, and brown coal is the most polluting form of coal, producing up to a third more greenhouse gas emissions per ton than conventional black coal when burnt.

Hannover Re did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

According to the 2020 analysis by Insure our Future, at least 23 insurers and reinsurers out of 33 analyzed by the group have introduced policies limiting or ending their support for coal projects and developments. However, several of these policies are not comprehensive. For example, while a number of insurers have ruled out supporting particular coal projects, many do not have full exclusions on companies that are developing coal plants.

“None of the top global insurers has committed to stop insuring the expansion of the oil and gas industry,” said Pinson at Reclaim Finance, “despite knowing this is the only solution if we want to keep warming below 1.5C. It would be shameful, though not surprising, if such loyalty is the result of a revolving door between both worlds.”

Other Big Emitters

DeSmog’s analysis also found significant ties among insurance directors to the world’s largest emitting companies as identified in the Climate Action 100+ (CA100+) list, an initiative created by investors to put pressure on the world’s biggest polluters to reduce their emissions.

The list includes the top one hundred companies with the highest emissions worldwide, such as BP, TotalEnergies, and Exxon, as well as 67 other companies which investors have identified as strategically important in reaching climate goals such as companies that provide support for these polluting industries. The list also includes the world’s highest emitting companies from sectors such as road transport, aviation, and shipping.

For example, nine percent of the 371 board members analyzed had past or current experience in the road transport sector overall.

Just over a quarter of Zurich board directors, for instance, had worked at some point in their career for the car industry, including for car companies and road developers. Three current board members of the Swiss insurer have current roles at car companies included on the CA100+ list, including Rolls Royce, Paccar Inc., and BMW, through board memberships and a role at a BMW-linked research institute.

Insurance board directors also had a few connections (6 percent among all analyzed) to other high-carbon industries such as aviation. The insurer with the most ties to aviation was France-based SCOR RE, where three board members had held roles in the industry. These include Fabrice Bregier, the former chief operating officer of CA100+ company Airbus; Bregier left the aircraft manufacturer in 2018. Meanwhile, AXA’s Jean-Pierre Clamadieu has been a director for Airbus since 2018.

Airbus is the world’s largest airplane manufacturer, and a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Planes sold by the company in 2019 and 2020 will produce over 1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide during their lifetimes, according to figures released by the company.

In response to a request for comment, a SCOR RE spokesperson said: “We have no comment to make at this time.”

Among the directors analyzed there was also a connection to shipping — an often overlooked yet highly polluting industry. Allianz supervisory board member, Jim Hagemann Snabe, is the current chair of global shipping company Maersk, the world’s largest shipping company which was responsible for an estimated 35.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions in 2018 and is also featured on the CA100+ list.

Allianz did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

Meanwhile, 15 percent of all board members analyzed had links to companies serving heavy industries including U.S. industrial giant and CA100+ company General Electric, which provides equipment to sectors including, oil, gas, coal, and power generation sectors, as well as in aviation and renewables. AndTokio Marine director, Akio Mimura, is former chair of Japan-based Nippon Steel, a CA100+ company and the world’s fifth largest steel-making company.

In addition, Renato Fassbind, a director at SwissRe, is a current director of Nestle, a CA100+ firm which also ranks among the world’s top ten plastic polluters according to research by Break Free From Plastic, a global movement of organizations and individuals looking to end plastic pollution.

Links to Lobbying

DeSmog also found several affiliations to powerful national and international lobby groups that have opposed attempts by some of the world’s most powerful governments to curb emissions.

In total, one in twenty directors have held roles in lobby groups and trade associations that have opposed climate measures. This includes Tokio Marine director Shinya Katanozaka who is vice-chair of Keidanren, widely considered to be Japan’s most powerful business group.

Keidanren was recently identified by analysts at climate thinktank InfluenceMap as one of the biggest obstructive forces to more ambitious climate action in the country. The business group represents major polluters in Japan and has repeatedly pushed for coal to remain a significant part of the country’s energy mix.

And between 2008 and 2010, Everest Re director John J. Amore was a director of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, one of the United States’ most influential business groups which has repeatedly opposed attempts by the U.S. government to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. An analysis of the trade body’s statements from 1989 to 2009 by social scientists found that the Chamber of Commerce had been a “powerful force in obstructing climate action,” in the country and that it had contributed to doubt over climate science.

Everest Re did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

Meanwhile, The Hartford director, Michael Morris, is a former director of the American Gas Association which has pushed against climate-focussed efforts to reduce emissions.

Fossil Financiers

The research also revealed directors who held senior roles in some of the world’s leading banks and investment vehicles that are under criticism from campaigners for their continued financial support for the fossil fuel industry.

Nearly a quarter of the directors analyzed have worked for financial institutions that have provided the most backing to fossil fuel projects since the Paris Agreement was signed, as ranked in the “Fossil Banks” list compiled by environmental non-profit BankTrack. For example, Bruce Carnegie Brown, chair of Lloyd’s of London since 2017, is vice chair of Spanish multinational bank, Santander, which according to BankTrack has given over $34 billion in financing to fossil fuel projects since the Paris Agreement was signed.

A spokesperson from Lloyd’s said the company was “accelerating its transition towards a more sustainable insurance and reinsurance marketplace, and has set out specific actions and commitments to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement. This includes asking managing agents to no longer provide new insurance cover for thermal coal-fired power plants, thermal coal mines, oil sands or new Arctic energy exploration activities from the end of this year.”

In addition to his current role at a coal-developing company, Swiss Re director Raymond K. F. Chi’en was, until 2007, a director of British bank HSBC which according to BankTrack lent $110.74 billion to the fossil fuel industry between 2016 and 2020.

All named directors were contacted for comment.

“Insurers often talk about the danger that climate change poses to their business,” said Shrago. This is particularly acute for property and casualty insurers right now, but in the long term will also impact life and health insurance companies Shrago said.

“You would think that given their long term perspective … [insurers] would think about the long term timing implications of their insurance and their investment businesses,” Shrago continued. “The fact that they don’t has always been something that is troubling and a little hard to understand. I think this report helps shed some light, maybe, on what’s going on.”

“Insurance companies must ensure that their boards are equipped to address the escalating climate crisis,” said Sulakshana. “That means hiring board members that are committed to serious oversight of climate risks and aligning their companies with a 1.5ºC pathway.”

Research by Ingvild Deila, Nadia Feldkircher, Mariangela Castillo, and Bo Frohlich.

COMMENTS