Here in my home state of Alaska, our long summer of record-breaking heat has finally come to a close. Even now, though, temperatures across the state remain well above average, with September representing yet another warmest-month-on-record in several locations.

But as Alaska’s temperatures begin to drop with the arrival of autumn, so, too does the national attention that fires and heatwaves briefly brought to the state. News outlets have moved on to other climate-related stories such as the fires in the Amazon and the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian. In the process they’ve missed the bigger picture: Rapid warming in Alaska remains among the most troubling disruptions of the global climate.

In fact, experts tell us, the warming underway in “the last frontier” isn’t just a local phenomenon. It’s deepening the global climate crisis.

Melting sea ice accelerates warming…and may disrupt global weather patterns

While Alaska’s record 90-degree temperatures captured national headlines this past summer, fewer media outlets noticed the epic loss of sea ice along the state’s western and northern coasts. This melting occurred most rapidly in the Bering Sea, which lies between northwestern Alaska and Russia.

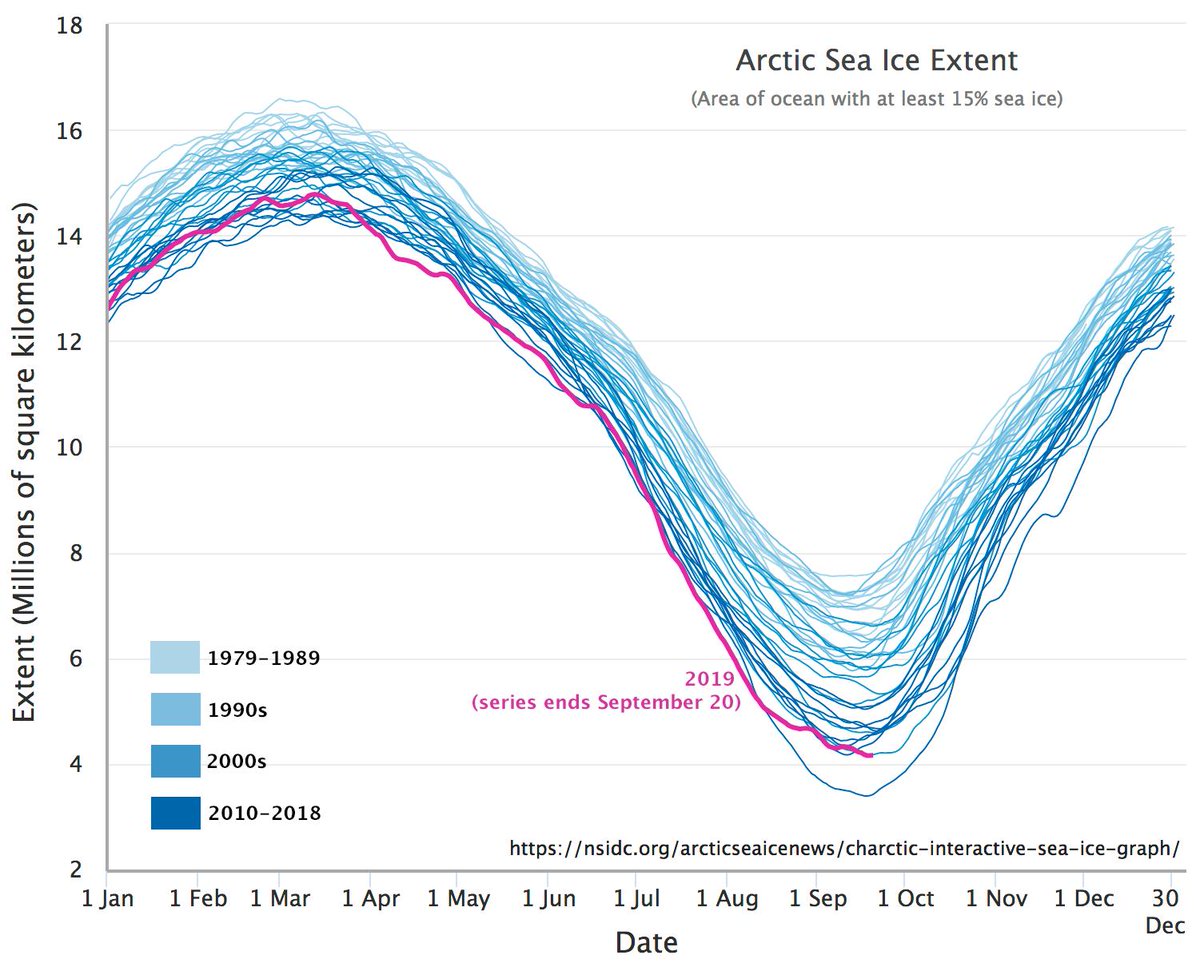

Sea ice here is the frozen ocean water that borders Alaska and adjoins the polar ice cap. It has been declining for years, but 2019 brought extraordinary melting that began in February, months ahead of norms. By August the ice had retreated over 150 miles from Alaska’s coast, an unprecedented distance that stunned long-time Arctic observers. Today, at a time when sea ice should be building back up, unusually warm air and ocean temperatures in many locations have delayed the autumn freeze.

In case you missed it, #Arctic sea ice likely hit its minimum extent for the year on September 18 at 4.15 million sq km (1.60 million sq mi). This year’s minimum is effectively tied for 2nd lowest in the satellite record with 2007 and 2016. Learn more: https://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/ ….

422:10 PM – Sep 23, 2019Twitter Ads info and privacy39 people are talking about this

“Temperatures in the Bering Sea are running around 5 degrees Fahrenheit above average right now,” says Brian Brettschneider, a climate researcher with the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “All that warmth needs to dissipate before ice can start forming again.”

As Brettschneider explains, delayed freezing at this time of year can set the stage for thinner sea ice throughout the winter, which can lead to earlier melting the following spring. This type of self-reinforcing process has long concerned climatologists. The temperature anomalies in the Bering also provide a striking example of the ocean warming that a recent United Nations report said is now occurring across the globe.

The loss of ice is already upending life in the Arctic by disrupting traditional access to fishing and hunting grounds, threatening coastal communities with erosion and increasing the potency of Arctic storms.

But bigger threats may lie ahead — scientists also believe disappearing sea ice is messing with global weather patterns, potentially increasing the ferocity of hurricanes and heat waves. As ice disappears, the temperature gradient decreases between the planet’s cold north and warmer southern regions. This evening-out of global temperatures has already started changing global wind patterns and climate scientists say it may contribute to the stalling of recent Atlantic hurricanes, including Harvey, Florence and the phenomenally destructive Dorian.

Meanwhile scientists have also attributed deep “wobbles” in the jet stream to Arctic warming. These “wobbles” may be intensifying heat waves like the one that brought dangerous 108-degree heat to Paris this summer.

Increasing wildfires torch the “legacy carbon” of northern forests

For many Alaskans 2019 was the summer of smoke.

In August wildfire smoke gave Anchorage the worst air quality of any U.S. city. Even in September, a month past the historical end of Alaska’s fire season, we still experienced road and school closures, evacuations, smoke and loss of property.

“For Alaska, the length of this year’s fire season was the stand-out part of the story,” says Brettschneider.

While the 2.5 million acres that burned in Alaska this year didn’t represent a state record, they still contributed to a record-setting fire season across the circumpolar North, with particularly large fires burning in Siberia. Researchers say the fires are part of a trend toward more frequent and severe Arctic blazes and a steadily lengthening fire season.

Alaska’s increasing wildfires matter globally for two entwined reasons. First, the millions of acres that now burn across the North pump carbon into the atmosphere, increasing global heating. In June alone Arctic fires released 50 megatons of carbon dioxide, more than the total annual carbon output of Sweden.

The kind of carbon being released also makes a difference. Arctic fires burn shrubs, tundra and extensive boreal forest. These types of areas contain up to 40 percent of the world’s land-based carbon, comprised of leaves, plants, roots and residue from previous fires, all lying in near-surface soils. But today’s hotter fires are burning this “legacy carbon,” a term researchers recently applied to carbon that has been safely sequestered for centuries. As this happens, a once reliable carbon sink becomes a source of carbon pollution.

Additionally, the increase in fire shortens boreal-forest burn cycles. Fires happen more often, burning down old trees and giving new trees less time to mature between conflagrations. As a result, forest composition has started transitioning away from old trees capable of storing more carbon to younger trees that store less. This shifting carbon balance, along with other factors such as thawing permafrost, may undermine the carbon-reduction goals that nations around the world have set under the Paris climate accord.

Alaska’s melting glaciers raise global sea levels

Receding glaciers have been a fact of life for my nearly 30 years in Alaska, but nothing I’ve seen compares to this past summer. Early in the season our glaciers lost their protective layer of winter snow, exposing bare ice to months of hot sunshine. This resulted in a hemorrhaging of meltwater that kept rivers roiling with the silty water of melting glaciers, even through a period of record drought.

“This is the continuation of a story that has been ongoing for several decades,” says Twila Moon, a research scientist with the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Moon explains that the comparatively low latitude of Alaska’s glaciers has made them vulnerable to melting for many years and that the amount of melting is a significant contributor to global sea-level rise.

Three studies published this year highlight the point. In one, an international research team estimated that the world’s mountain glaciers, which do not include the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, lost a hard-to-fathom 9,000 billion tons of ice over the past 50 years. Researchers further estimated that melting of mountain glaciers, which only constitute about 4 percent of land ice worldwide, fueled up to 30 percent of global sea-level rise throughout the 20th century. They pegged Alaska’s glaciers as the largest single contributor to the melting among the world’s mountain glaciers.

Another study of mountain glaciers predicted that, at current levels of fossil fuel use, Alaska would lose up to 50 percent of its remaining glacier ice in the coming decades, continuing the state’s role as the leading source of melting outside of Greenland and Antarctica. The study predicts another 10 inches of global sea-level rise from mountain glaciers alone — enough to drown low-lying coastal areas from Florida to Bangladesh.

A third study suggests scientists may still underestimate the speed of melting glaciers. By using underwater sonar surveys of Alaska’s LeConte Glacier, researchers discovered melt rates more than two orders of magnitude greater than previously predicted. If the findings test positively elsewhere, this type of melting may boost the estimated contribution of glaciers to rising seas.

The studies put tangible numbers on just how much sea-level rise is a result of Alaska’s famously melting glaciers. Perhaps the most worrisome of all climate change impacts, rising seas threaten to displace hundreds of millions of people from coastlines across the world, sparking famine, conflict and other human migration crises.

Thawing permafrost and the carbon bomb

Slumping roads, sinking buildings, “drunken” forests comprised of leaning or toppled trees — if you live in Alaska, you know these as telltale signs of thawing permafrost.

Lowly permafrost is an often-unsung hero of carbon storage. Frozen in place by millennia of long, frigid winters, it consists of deep layers of leaves, bones, soil, mammoth tusks and other organic material — even caribou poop — that have accumulated in an undecomposed state over time. Scientists have long considered permafrost to be, like boreal forests, a permanent source of sequestered carbon.

Alaska’s permafrost has been thawing for decades. But sharply rising temperatures evidenced by this past summer’s heat have accelerated the change.

As Alaska climatologist Rick Thoman recently wrote on Twitter, “winters in Alaska aren’t what they used to be.”

Researchers at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks have documented permafrost warming enough to push near-surface soils above the freezing mark, even in deep winter. Researchers from Canada to Greenland to Siberia have observed similar warming.

In Alaska the thawing causes erosion that damages roads and other infrastructure and even threatens the survival of entire communities.

But the effects will also be felt on the global scale. The widespread decomposition triggered by this thawing threatens to release massive amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas many times more potent than carbon dioxide. Scientists estimate this so-called “carbon bomb” could eclipse the annual emissions of China, the world’s largest polluter, and further undermine global efforts to reduce carbon.

It would also pose a staggering financial burden. Researchers earlier this summer estimated thawing permafrost will add $70 trillion to the global cost of climate change, an expense that will be borne most by the world’s poorest people.

Alaska’s warming is also the world’s

The rapid warming of Alaska has become a global spectacle, and experts tell us that its impacts will be felt around the world in the years ahead.

In part that’s due to the self-reinforcing nature of the processes now underway, where less sea ice begets less sea ice, more fire leads to more fire, and thawing permafrost jeopardizes the remaining permafrost.

It’s also due to the nature of the Arctic, which scientists increasingly see as a vital source of cooling for the entire planet. As that system destabilizes, livable climates elsewhere are put at risk.

But maybe all of that warming has inspired something, too. As research scientist Twila Moon observes, the public now appears more aware of the important roles played by glaciers and how their melting impacts drinking water supplies, agriculture, global sea-level rise and more.

“I’m really heartened about the increased awareness about climate change,” she says.

But Moon also cautions that there’s still a long way to go in terms of both awareness and action — not just in Alaska, but around the planet.

“We’re not at the level we need to be, given how fast the change is occurring,” she says.

COMMENTS